Did Charles Dickens write about New Hall Mill?

On May 18th 1867, Charles Dickens published a lengthy article about the supposed murder of a Langley Heath girl, Mary Ashford, in 1817, and the subsequent trial of a young man named Abraham Thornton.

The murder took place on Penns Lane - the B4148 - which is quite close to New Hall Mill, and in his account, Dickens referred to Twamley's Mill - that's the name of our miller at New Hall! Could Dickens really have written about New Hall Mill?

Certainly, when I read his words, I felt confident that Dickens was referring to New Hall Mill, however, although New Hall Mill was operated by one of the Twamley family at that time - the third William Twamley at New Hall (1763 - 1825) it wasn't a foregone conclusion.

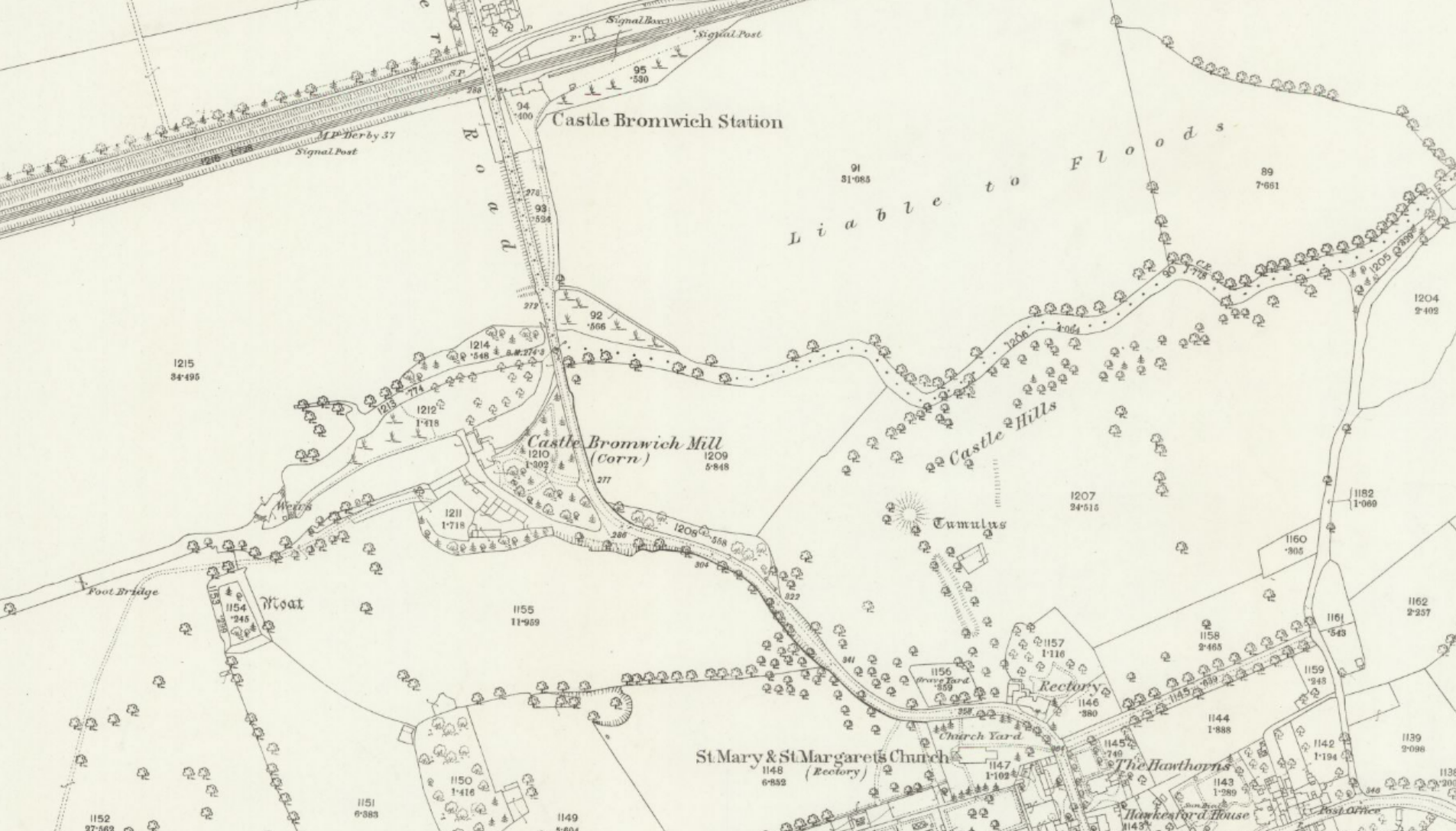

With a bit more research, it turned out that Dickens was referring to nearby Castle Bromwich Mill, where the miller was our William Twamley's brother, Zachariah Twamley (1772 - 1856). Castle Bromwich Mill was on the south bank of the River Tame, near the bottom of Mill Hill, in Castle Bromwich. The site is now covered by the roundabout for junction 5 of the M6 motorway.

The text also mentions Penns Mill, which was the nearest mill to New Hall Mill. It was along the same brook as New Hall Mill, and built on land belonging to New Shipton Farm, where our millers traditionally lived.

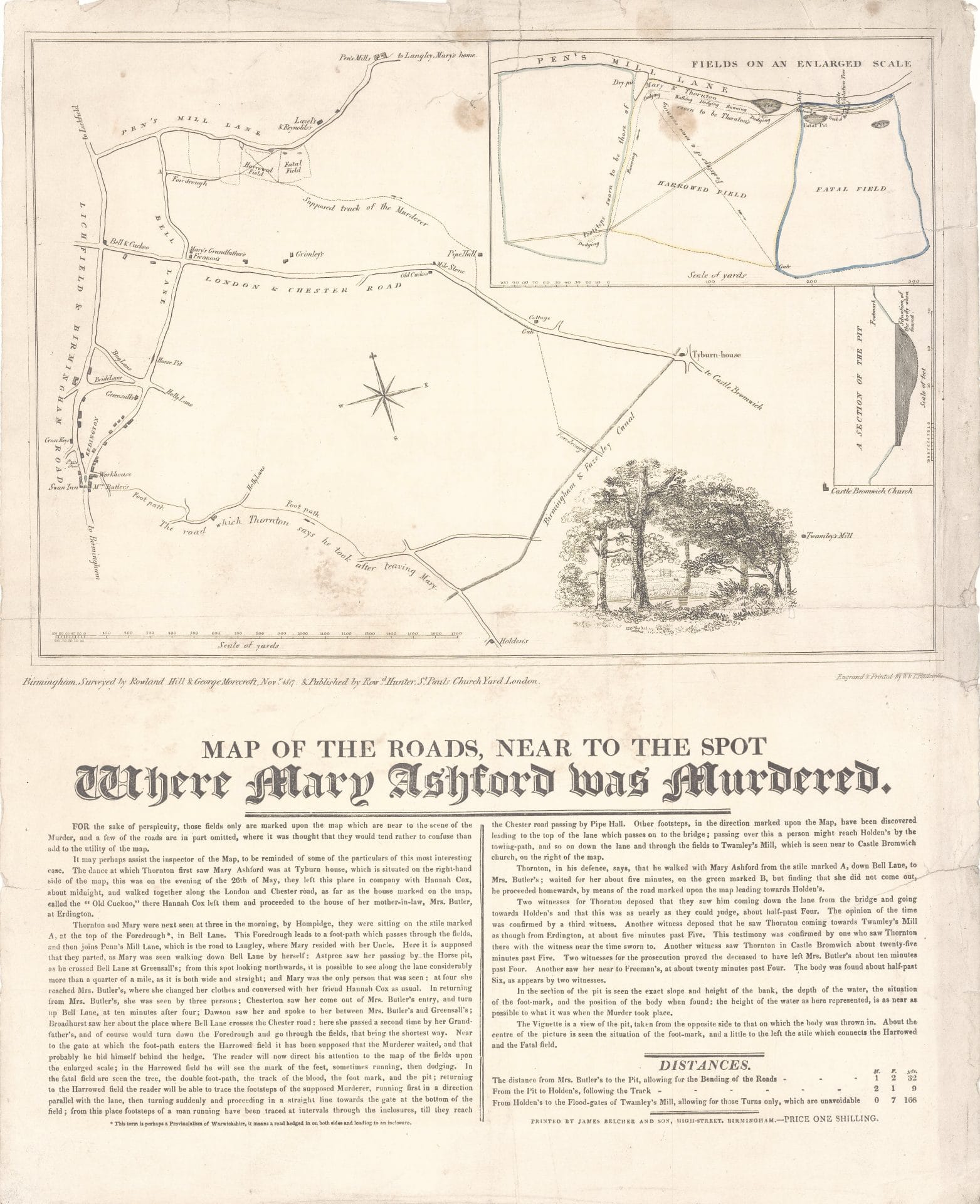

Dickens refers to a 'hot-pressed map' which may be the map below, "Map of the Roads, near to the Spot Where Mary Ashford was Murdered" by Rowland Hill (1795-1879) & George Morecroft, published in 1817. An original of this map is (at the time of writing) for sale by Antiquariat Dasa Pahor GbR, München, Germany. The map confirms that the Twamley's Mill referred to by Dickens was Castle Bromwich Mill, not New Hall Hill. You can see Twamley's Mill marked to the right of the engraving of the wood. However, its relationship to Castle Bromwich Church is not quite correct - it should be to the north west of the church, close to the Tyburn road.

Dickens' article was published in his journal, 'All the Year Round', in 1867.

Here is the story of Mary Ashford as he retold it. I have highlighted the references to Mills in the text and edited out some of the more technical and lengthy descriptions and analyses. If you wish, you can read the full text here.

Wager of Battle - the Trial of Abraham Thornton for the Murder of Mary Ashford

Charles Dickens

On a bleak acclivity seven miles to the north-east of that vast centre of industry, Birmingham, there is a small town named Sutton Coldfield, a place of about four thousand inhabitants. On Monday, the 26th of May, 1817, Mary Ashford, a blooming girl of about twenty years of age, acting as servant to her uncle, a small farmer named Coleman, who lived at Langley Heath, in the parish of Sutton Coldfield, and three miles from Erdington, prepared to start for Birmingham market on some errands for the family.

This servant-girl, standing before the bedroom glass in her pink frock, scarlet spencer, and little straw bonnet streaming with primrose-coloured ribbons, was in more than a girl's usual flutter of pretty vanity and holiday excitement; for that night, being Whit-Monday night, there will be the annual club-feast and dance at Tyburn House (an inn), a mile from Erdington, and she will meet there all the young beaux of half a dozen miles round, and, above all, a young man whom she has often seen on Sundays — that thick-set, sturdy young bricklayer, Abraham Thornton, a farmer's son at Erdington. Smiling at her own pretty reflexion in the glass, Mary Ashford looks over her shoulder (after the manner of girls) to see that her shawl sets well, ruffles out her bonnet-bows, and, with little quick bird-like touches, arranges her glossy hair and the set of her pink gown. Then she ties up in a bundle her clean frock, white spencer, and white stockings, for the dance in the evening. She trips away at last, with a merry laugh at her uncle's warnings to be home early, and runs singing down the lane, happy and innocent as a bird the first day it can use its wings. At about ten o'clock that May morning, when thrushes are singing, hedges flowering, and everything is happy and rejoicing, Mary Ashford calls on her friend, Hannah Cox, servant to Mr. Machin, to leave her bundle at her (Hannah's) mother's, who lived opposite. She is to call in the evening on her way from market, change her dress, and go to the dance at Tyburn with her friend. At about six Mary Ashford returns, changes her dress, dons the clean coloured frock and the white spencer, puts on a new pair of Hannah's shoes, and between seven and eight sets out, full of anticipation, pretty girlish chatter, and surmise.

The club-feast at Daniel Clarke's inn (Tyburn House — ill-omened name) was, like all other club-feasts, as bad a place for an innocent young woman as could well be. The house would ring with tipsy shouts, the windows shake with the competing shuffles of the dancers. They are always alike, these club-revels: owlish old men sit outside on the ale benches, the young wild striplings of the place, half drunk, are bragging and quarrelling; the low-roofed room is reeking with smoke; the ale is passing round much too fast; the language is coarse; all but the women are fevered or besotted with beer. Nothing healthy or honest about the amusements, but, on the contrary, everything degradedly stupid, drunken, "raffish," and debasing.

Hannah Cox, rather frightened at the revel, remained up-stairs with her sister, and only stayed in the lower room a quarter of an hour, just to see a dance or two, and who was there. She did not observe Thornton. But the dancing-room had some magnetic attraction for poor Mary, and she remained there all the time. A little before eleven, Hannah thought it time for respectable girls to go, and came down to look for Mary. She met her at the door of the room, when Mary said she would not be long, but would come to her soon. Hannah then walked about twenty yards on the road, and waited on the bridge. Presently a man named Benjamin Carter came out, and Hannah, getting restless, sent him in to call Mary. Soon after, Mary came out with Abraham Thornton. She was going to sleep at her grandfather's, and walked homewards first, followed by Carter and Hannah. Carter walked a little way further, and then went back to the revel. Near an inn called the Old Cuckoo, Hannah lost sight of Mary and her young man.

On reaching her mother's house at Erdington, Hannah went calmly to bed. In the morning, twenty minutes to five by the cottage clock, Hannah was awoke by a knocking at the door. She went down, and found it was Mary Ashford, calm and in good spirits, and in the same dress as she had danced in the night before. As Mary

changed her dress and put on again the old pink frock and scarlet spencer in which she had gone to market on the day before, she told Hannah she had slept at her grandfather's at the top of Bell lane. She then wrapped her boots up in her pocket-handkerchief, tied the rest of her dress and some marketing things in a napkin, and, after staying about a quarter of an hour chatting, went away.

Poor Mary, no longer honest, no longer pure, no longer happy, had deceived Hannah. She had not slept at her grandfather's; she had been about the whole night, rambling here and there with Thornton. John Humpidge, a labourer of Whitton, leaving a friend's house at Penn's Mills about a quarter before three, saw Thornton and a girl at the "ford-rift," at a stile leading into Bell-lane. Humpidge wished Thornton good morning, but the girl held her head determinately down, and the bonnet hid her face. This girl was Mary Ashford; of that, there can be no doubt. It is beyond dispute. Thomas Aspre, a man of Erdington, on his way to Birmingham that morning, crossed Bell-lane, leaving it on his right, and Erdington on his left. It was about half-past three; he then saw Mary alone, walking very fast past a horse-pond in the lane, in the direction of Mrs Butler's, at whose house she called to change her dress. At about four the lost girl was seen by another Erdington labourer, named Dawson, coming from Erdington. John Kesterton, a farmer's man at Erdington, who had got up soon after two to "fettle" his horses, put them to the waggon at four, and watered them at the pond in Bell-lane. At a quarter-past four Kesterton turned the horses round, and made straight for Birmingham, through Erdington. Turning to look back a little past Mrs Butler's by some chance impulse-for the road was quiet and lonely enough at that hour-he saw Mary Ashford, whom he knew well, coming out of the entry to widow Butler's cottage. He smacked his whip to make her turn, and she turned and looked at him. No one was with her. She turned up Bell-lane, and seemed to be in a great hurry. She had on a straw bonnet and a scarlet spencer, and carried a bundle in her left hand. The road she took led both to her grandfather's, where she ought to have slept, and her uncle's, to whom she was servant.

At five o'clock, George Jackson, a Birmingham gun-borer, who had left Moor-street, Birmingham, on his way beyond Penn's Mills to seek work, came past the workhouse at Erdington. He turned out of Bell-lane about half-past six into the ford-rift leading to Penn's Mills, going along the foot-road till he came to a pit close by the footpath. As he came near it he observed, to his extreme horror, in the pure morning sunlight, a bonnet, a pair of shoes, and a bundle, close by the slope, that overhung the pit; one shoe was all over blood. The pit was in a grass-field separated from the carriage-road only by a hedge, and near a stile. The things were about a foot below the top of the slope, and about four yards below spread the dark water of the pit-mouth. There had evidently been a murder, and the body must lie weltering in that pool. Kesterton, [did Dickens mean Jackson?] frightened, instantly ran to Penn's Mills, half a mile off, for assistance; but at the nearest house, finding a man named Lawell coming out, he told him to stop and guard the things while he ran to the mills. Some labourers came from the mills and passed an eel-rake through the water. Yes, there it was-a woman's body, duckweed and leaves and mud on the pale cold face. It was poor Mary Ashford, recognised in a moment by her scarlet spencer and pink gown; murdered beyond a doubt; her clothes were steeped in blood. She had been abused, then murdered. That was the universal belief.

One of the workmen at Penn's Mills instantly went along the harrowed field beyond the pit to see if he could trace the footsteps of the poor girl and her murderer. Going to the pit from Erdington there were footprints of a woman and a man; they were close together, and appeared like the footprints of persons running, both by the stride and the depth of the impressions. Near the pit, the footprints doubled backwards and forwards, as if one person had chased the other. The footsteps were trackable on the grass, but not on it, and were visible on the harrowed ground. The prints were traceable on the grass by a dry pit, then towards a water-pit in the harrowed field. The woman's steps were nearest the pit. The footprints of a man were also visible the contrary way, as if running back on the harrowed ground to the gate at the far corner across the footpath, which led across a clover-field towards Pipe Hall, and by a short cut to Castle Bromwich. There was a man's footprint near the edge of the declivity; there was blood about forty yards off the pit, and some as near as fourteen yards; there was also a track of blood lying thick upon the clover in the direction of the pit. The footpath was about one hundred and forty yards from the dry pit on one side, and the wet pit on the other.

Thornton was instantly arrested, and examined at Tyburn, the scene of that unhappy revel. He owned to guilty association with the girl, and at once made the following statement:

He said he was "a bricklayer; that he came to the Three Tuns at Tyburn about six o'clock the night before, where there was a dance; that he danced a dance or two with the landlord's daughter, but whether he danced with Mary Ashford or not he could not recollect. Examinant [Thornton] stayed till about twelve o'clock; he then went with Mary Ashford, Benjamin Carter, and a young woman, whom he understood to be Mr Machin's housekeeper, of Erdington; that they walked together as far as Mr Potter's; Carter and the housekeeper went on towards Erdington, examinant and Mary Ashford went on as far as Mr Freeman's; they then turned to the right, and went along a lane till they came to a gate and stile on the right-hand side of the road; they then went over the stile, and into the next piece, along the foot-road; they continued along the foot-road four or five fields, but cannot exactly tell how many. Examinant and Mary Ashford then returned the same road; when they came to the gate and stile, they first got over; they stood there ten minutes or a quarter of an hour talking; it might be then about three o'clock. Whilst they stood there a man came by (examinant did not know who); he had on a jacket of a brown colour; the man was coming along the footpath they had returned along; examinant said, 'Good morning,' and the man said the same; examinant asked Mary Ashford if she knew the man; she did not know whether she knew him or not, but thought he was one who had been at Tyburn; that examinant and Mary Ashford stayed at the stile a quarter of an hour afterwards; they then went straight up to Mr. Freeman's again, crossed the road, and went on towards Erdington, till he came to a grass-field on the right-hand side of the road, within about a hundred yards of Mr Greensall's, in Erdington; Mary Ashford walked on; examinant never saw her afterwards. It was nearly opposite to Mr. Greensall's. Whilst he was in the field he saw a man cross the road to James's, but he did not know who he was; he (Thornton) then went on for Erdington Workhouse to see if he could see Mary Ashford; he stopped upon the green about five minutes to wait for her; it was four o'clock, or ten minutes after four o'clock. Examinant went by Shipley's, on his road home, and afterwards by John Holden's, where he saw a man and woman with some milk-cans, and a young man driving some cows out of a field, whom he thought to be Holden's son. He then went towards Mr Twamley's mill, where he saw Mr Hatton's keeper taking rubbish out of the nets at the flood-gates. He asked the man what o'clock it was; he answered, 'Near five o'clock, or five.' He knew the keeper. Twamley's mill is about a mile and a quarter from his father's house, with whom he lives. The first person he saw was Edward Leake, a servant of his father's, and a boy; his mother was up. He took off a black coat he had on, and put on the one he now wears, which hung up in the kitchen, changed his hat, and left them both in the house; he did not change his shoes or stockings, though his shoes were rather wet from having walked across the meadows. That examinant knew Mary Ashford when she lived at the Swan at Erdington, but was not particularly intimate with her; that he had not seen Mary Ashford for a considerable time before he met her at Tyburn. Examinant had been drinking the whole evening, but not so much as to be intoxicated."

Abraham Thornton, against whom public opinion ran high, was tried for the murder of Mary Ashford, before Mr. Justice Holroyd, at the Warwick assizes, on August 8th, Mr Reynolds appearing for the defence. [...]

The distances were most material in the case, and must be examined before Thornton's case can be fully understood. [...] This calculation, which is bound on all sides by the most stringent observation, left only eleven minutes for the deceased's walk from Butler's house to the pit, for the assault, the death, and the struggle, after a pursuit (as the prosecution surmised), and the carrying the girl's body thirty yards to the pit, and placing the bundle and shoes on the slope. To do all this, Thornton, a stout short man with clumsy legs, must have leaped over the country at the rate of fifteen miles an hour. It was also proved that deceased had no wound or bruise upon her, and that the blood found proceeded from natural causes. Mr Sadler, the prisoner's solicitor, complained much at the time of the cruel reports spread against Thornton, the pamphlets and songs, that rendered it difficult to find an unbiased jury. The county magistrates themselves were strongly prejudiced against Thornton, and had pursued their investigations with the acrimony of partisans, who had quite made up their mind that Thornton had abused and murdered Mary Ashford after she left Butler's house; although it was proved (by circumstances which we need not recapitulate) that Thornton and the girl had been together all night, and that Mary Ashford had returned to her friend with a lie in her mouth, smiling, and without a word of complaint. [...]

There was no sign of a struggle near the pit, and although there were two labourers' houses within a hundred and fifty yards of the pit, and men were beginning to stir for milking, bird-minding, and stable-cleaning, there were no cries for help heard, notwithstanding Mary Ashford was a vigorous and robust girl in the prime of life.

The prisoner's conduct after leaving Mary Ashford was quiet and straightforward. He got home about five. He then changed his black coat for a damson-coloured one, but did not change his shoes or stockings, though the former were wet. When arrested at ten o'clock, he at once confessed he had spent all night with Mary Ashford, but said he had left her near Butler's, and after having waited five minutes for her on Erdington-green. There was nothing to impugn this statement, and Thornton was acquitted by the jury. [...]

Public feeling was far too much set on Thornton's death, to be satisfied with this verdict of acquittal. A letter-press description, strongly coloured, together with a sketch of the pit and a drawing of Mary Ashford, were published by Mr. Lines, and engraved by Mr. Radcliffe, of Birmingham. A hot-pressed map (15 by 11) also appeared and "An Antidote to Prejudice" was followed by "An Investigation of the Case." The Rev Luke Booker also published a moral review of the conduct and case of Mary Ashford, in refutation of the arguments adduced in defence of her supposed violator and murderer, which concluded with:

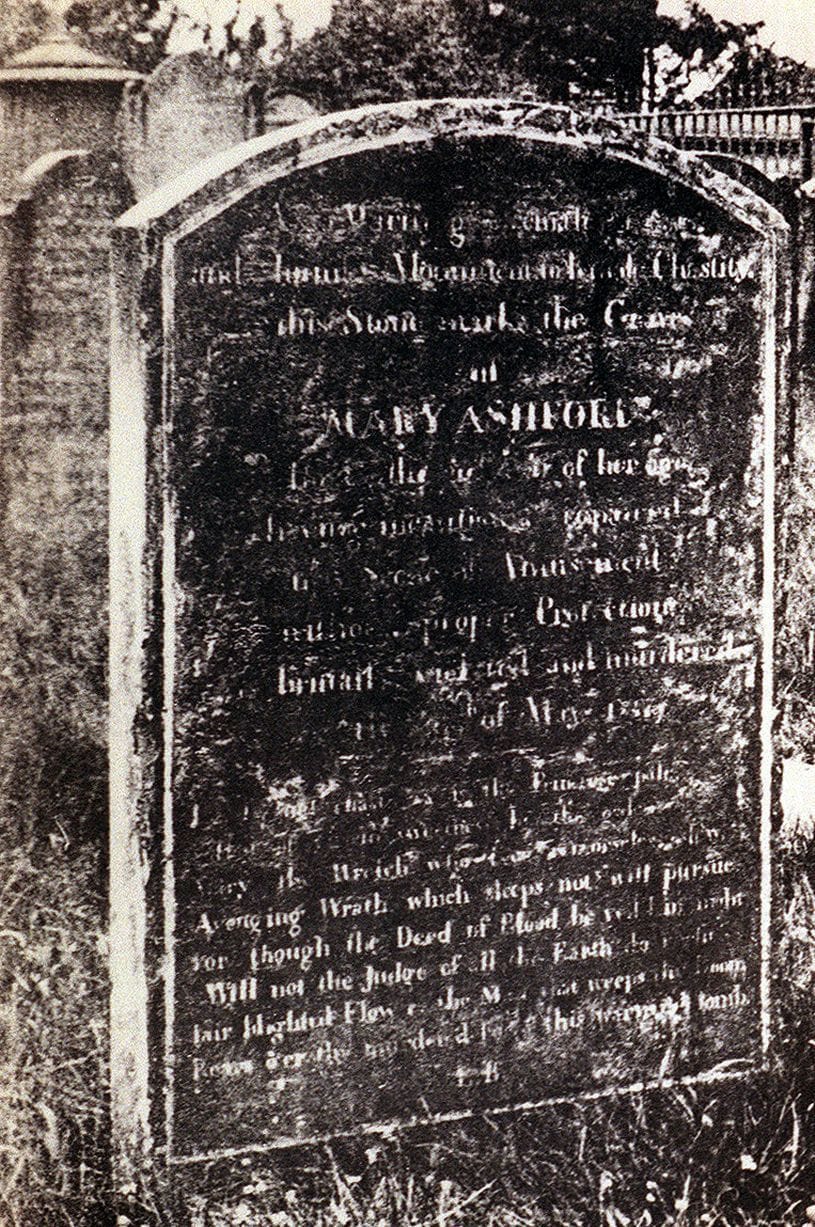

"A proposed Epitaph. - As a warning to female virtue, this monument is erected over the remains of Mary Ashford, a young woman chaste as she was beautiful, who, in the twentieth year of her age, having incautiously repaired to a scene of amusement, without proper protection, was brutally violated and murdered on the 27th of May, 1817, in the parish of Aston.

Lovely and chaste as is the primrose pale,

Rifled of virgin sweetness by the gale,

Mary! The wretch, who thee remorseless slew,

Will surely God's avenging wrath pursue.

For, though the deed of blood be veiled in night,

'Will not the Judge of all the earth do right?'

Fair blighted flower! The muse, that weeps thy doom,

Rears o'er thy sleeping dust this warning tomb!"

To answer the last-named work there was published, "A Reply to the Remarks of the Rev Luke Booker, LL.D., in a pamphlet entitled 'A Moral Review of the Conduct and Case of Mary Ashford, &c.' By a Friend to Justice."

There also appeared, "Observations upon the case of Abraham Thornton, &c.; showing the danger of pressing presumptive evidence too far, together with the only true and authentic account yet published of the evidence given at the trial, the examination of the prisoner, &c. And a correct plan of the locus in quo. By Edward Holroyd, of Gray's Inn."

There were also two very wild dramas on the subject: one of them entitled "The Murdered Maid; or, The Clock Struck Four! A drama in three acts." The other, "The Mysterious Murder; or, What's the Clock? A melodrama in three acts. Founded on a tale too true."

Funds were procured, and a clever local solicitor, raking up an old unrepealed statute, induced the brother of Mary Ashford, as her heir, to take proceedings for an "appeal of murder" against Abraham Thornton, who was arrested by the sheriff of Warwick on the 1st of October. On the 16th of November term, William Ashford appeared in the Court of King's Bench, at Westminster, as appellant, and Abraham Thornton was brought up on a writ of habeas corpus as appeller. [...] Ashford was a short slight-made young man of twenty, with sandy hair and blue eyes; Thornton, a short, very fat, robust man, with full cheeks, fresh complexion, and a confident smile on his by no means forbidding countenance. [...]

There was a vague feeling that the old trial by ordeal was to be revived—single combat in the lists - a tournament in full plate armour, with trumpets blowing, and the law-judges standing by to cheer on the two combatants. [...]

Mr Le Blanc concluded the reading of the record by saying, "Are you guilty or not guilty of the said felony and murder whereof you stand so appealed?" Mr Reader now put into the prisoner's hand a slip of paper, from which he read, "Not guilty; and I am ready to defend the same with my body." Mr Reader had likewise handed a pair of large gauntlets or gloves to the prisoner, one of which he put on, and the other, in pursuance of the old form, he threw down for the appellant to take up. The glove was not taken up. Ashford's counsel disputed the right of Thornton to "wager of battle," and were ready to fight it out with tongues and not spears.

Mr Le Blanc: Your plea is, that you are not guilty, and that you are ready to defend that plea with your body?

The prisoner: It is.

The appellant then stood up in front of Mr Clarke.

Lord Ellenborough: What have you got to say, Mr. Clarke?

Mr. Clarke: I did not expect, my lord, at this time of day, that this sort of demand would have been made. I must confess that I am surprised that the charge against the prisoner should be put to issue in this way. The trial by battle is an obsolete practice, which has long since been out of use, and it would appear to me extraordinary indeed, if the person who has murdered the sister should, as the law exists in these enlightened times, be allowed to prove his innocence by murdering the brother also, or, at least, by an attempt to do so.

Lord Ellenborough: It is the law of England, Mr. Clarke; we must not call it murder.

Mr Clarke: I may have used too strong an expression, my lord, in saying murdering the brother; but, at all events, it is no less than killing. I apprehend, however, that the course to be taken is in a great measure discretionary; and it will be for the court to determine, under all the circumstances, whether they will permit a battle to be waged in this case or not.

Mr Clarke then put in a counter-plea that the applicant was incompetent, from youth and want of bodily strength, to fairly meet the appellee in battle, and trusted the court would waive the right of battle, and direct a new trial by jury.

On November 22nd the case again came on, and Ashford counter-pleaded that there were circumstances which induced the most violent presumption of Thornton's guilt, and that in such cases the law was that he could not be permitted to wage battle, but must be tried by his country. The proceedings were then postponed till the next term. [...]

On the 24th of January, 1818, the vexed case was again tried. Thornton replied, stating all the facts in his favour, and claiming a right to the combat. [...]

On April 10, Lord Ellenborough gave the final decision. He said:

"[...] At present we pronounce that there be trial by battle, unless the appellant show reason why the defendant should not depart without a day."

On April 21, Ashford not having accepted the wager of battle, the appeal was urged, and Thornton was discharged. The crowd were so threatening and turbulent, that he had to be concealed in a private room until they dispersed.

This was the last instance of trial by battle being demanded in an English court. In the following session, the rusty old act of parliament under which the appeal was made, was repealed. Wager of battle had only been snatched up as a weapon of defence, exciting as great astonishment in Thornton's adversaries as the bows and arrows used by a Tartar regiment at Austerlitz produced on the Grenadiers of Napoleon. It is a pity that our statute-book should still contain pages as mischievous and dead as that page of whose removal we have given the brief history.

Dickens concludes:

Poor Mary Ashford's grave at Sutton Coldfield is still a place of pilgrimage for holiday visitors from Birmingham. The tombstone, with the epitaph before given, was erected by subscription. [This was erected in Holy Trinity Church, Sutton Coldfield]. As for Thornton, who had up to this time been respected at Erdington, he went to America, where he followed his trade of a bricklayer, married, had children, and died some years ago. In the January only of this very year (1867), William Ashford, the brother of the murdered girl, and for many years a fish-hawker, was found dead in his bed in New John-street, Birmingham. He was seventy years old. The causes of Mary Ashford's death, only the Last Day can now reveal.

And there Charles Dickens ends his account. Mary Ashford's grave at Holy Trinity Church no longer stands where it once did, as many of the headstones were removed to the perimeter of the churchyard after WW2, and some were destroyed.

Using the map above, published in 1817, here is the approximate location where Mary's Ashford's body was found.

The three pits on the south side of Penns Lane can clearly be seen in this 1887 Ordnance Survey map.

If your appetite has been whetted by Dickens' account, you can read more about the case here.