Wheat in the UK past and present

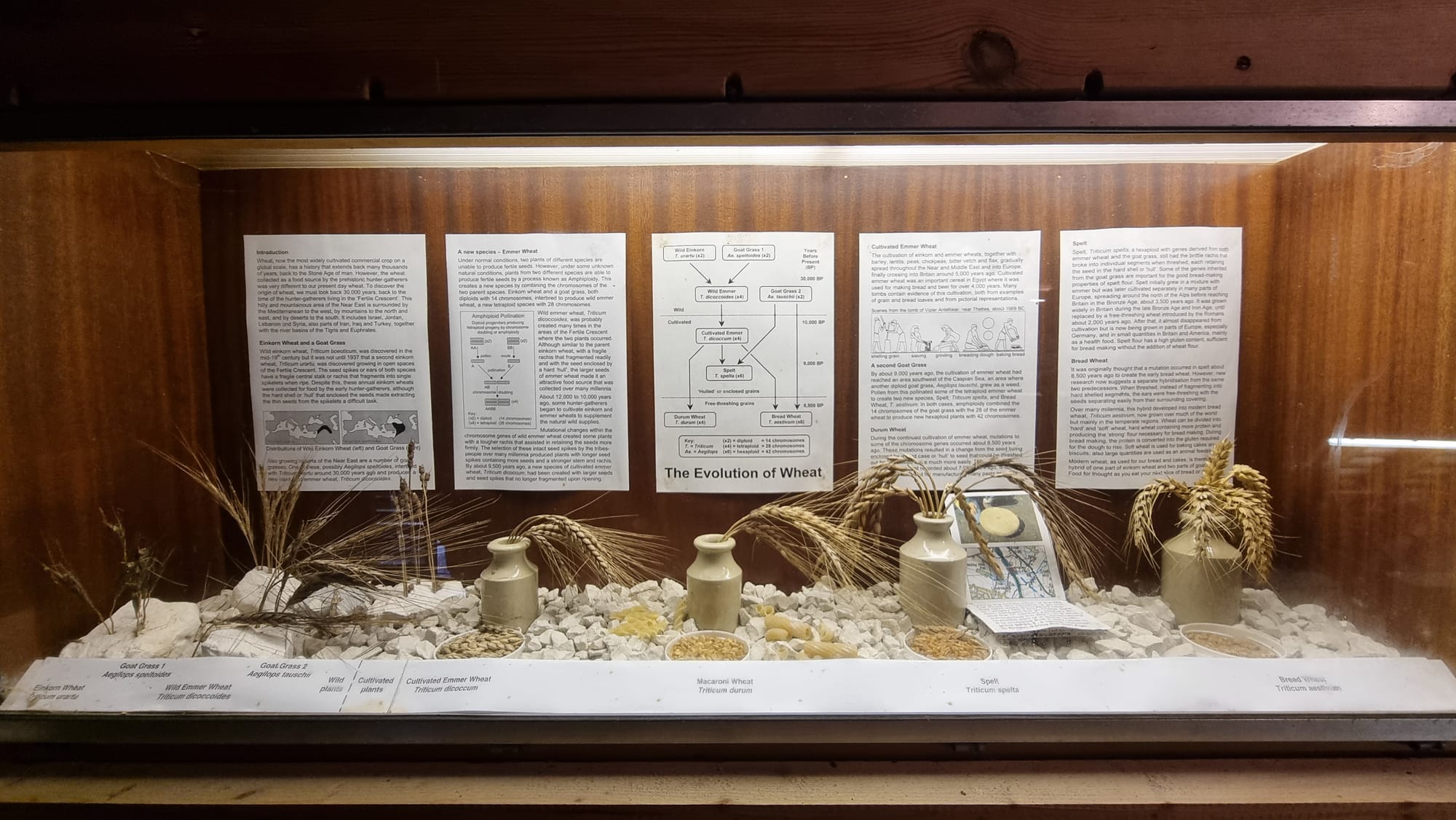

The Evolution of Wheat

Wheat has come a long way from its early origins, evolving from wild grasses thousands of years ago into the varieties we know today. Thousands of years ago, Wild Einkorn crossed with Goat Grass, creating Emmer wheat. Early humans started gathering and growing this wheat around 10,000 years ago, unknowingly selecting plants with larger grains, which eventually led to the development of Cultivated Emmer.

As Emmer spread, it mixed with other wild grasses, leading to Spelt, an ancient form of wheat with tough outer shells. Over time, a mutation made it easier for grains to fall from the wheat head, making it easier to harvest. This mutation helped wheat evolve into the free-threshing Bread Wheat we use today. Meanwhile, Emmer also gave rise to another type of wheat, Durum Wheat, which grows best in hot, dry areas like the Mediterranean, North Africa, and parts of the American Southwest. Its hard grains are ground into semolina flour, perfect for making pasta.

The Wheat Genome and Growth

Today, we can trace these changes through wheat’s genome. Wheat’s genes are located on chromosomes, and Bread Wheat has 42 chromosomes, formed from three wild grasses over thousands of years. When wheat reproduces, it passes these chromosomes on to its seeds.

Originally, wheat plants were very tall. In fact, in the 1500s, artist Pieter Bruegel depicted wheat as towering over the harvesters in his painting The Corn Harvesters.

But modern farming machines struggled with tall wheat, so scientists used shorter wheat varieties found in Japan to develop wheat with genes that keep the plants shorter and easier to harvest. These shorter plants also tend to produce more grain. Some of these wheat types came from landraces - plants that adapted to specific local conditions over time.

Categories of Wheat

Wheat can be divided into two groups, with awns or bristles, or without awns. Most of the wheat grown in Britain is awnless, but awned wheat, usually called 'bearded wheat', is becoming more common as newer varieties are introduced. These may include varieties that have been bred in other parts of the world, such as Germany, where bearded wheat is more common. You may see varieties with smaller, compact ears, or 'lax' varieties, with the flower heads spaced out along the ear.

Wheat can also be divided into 'hard' wheat and 'soft' wheat.

- Hard wheat, containing more of the gluten proteins gliadin and glutenin produces the 'strong' flour necessary for the dough to rise when bread making.

- Soft wheat can be used for baking cakes, pastries and biscuits and for the newer industry of alcohol production.

Bread Wheat

Bread wheat is now one of the most widely grown crops in the world, and it thrives in regions with mild to cool climates, including the UK, Europe, North America, and Australia. In the UK, Bread Wheat is the dominant type, making up about 95% of all wheat grown. It’s used in a wide range of foods, including bread and other baked goods.

Over time, new varieties of bread wheat have been developed to grow more efficiently and produce higher yields, which has led to older varieties becoming less common. This is why places like the John Innes Centre in Norwich store seed collections to preserve traditional wheat varieties.

Though Bread Wheat is the main type grown in the UK, older varieties are still grown on a smaller scale.

Rivet wheat, once popular in southern France, Spain, and Italy, is now rarer but still cultivated in small areas. Other rare types, such as Vavilov wheat from Armenia and Macha wheat from Georgia, are mainly preserved for their unique traits.

Why traditional varieties matter

While most wheat today focuses on high yields and baking quality, these older varieties remain important. They may contain valuable traits like disease resistance or drought tolerance, which could help improve wheat crops in the future, including in the UK. By preserving these traditional types, we ensure that we have access to a range of wheat varieties that might help address challenges in growing wheat in different conditions.

Milling Groups

In the UK, wheat varieties are classified into Groups 1 to 4 based on their bread-making and milling quality, as defined by the AHDB (Agriculture and Horticulture Development Board). Group 1 wheat varieties are considered the highest quality for bread-making. They have:

- Strong gluten content, ideal for dough strength and loaf volume

- Consistently high protein levels (usually over 13%)

- Excellent milling and baking performance

- Preferred by millers and bakers for producing quality flour for bread

Because of their premium quality, Group 1 wheats often command a higher market price and are grown specifically for the milling industry. Examples include varieties like Crusoe, Skyfall, and Solstice.

UK Wheat Harvesting

As of the 2024 harvest, the UK produced about 11.1 million tonnes of wheat. This represented a 20% decrease from the previous year and is the smallest wheat harvest since 2020, primarily due to adverse weather conditions affecting both planting and yields.

The harvested wheat is used in various ways:

- Food Production: A substantial portion is processed into flour for bread, pasta, and other baked goods.

- Animal Feed: Lower-quality wheat is often used as livestock feed.

- Industrial Uses: Some wheat is employed in biofuel production and other industrial applications.

Due to the reduced domestic yield, the UK has increased wheat imports to meet demand, which may influence food prices and raise concerns about food security.

A newer use for wheat is for the production of alcohol. Wheat grains are pressure cooked to release the starch granules. The resulting liquid is fermented followed by distillation to recover the alcohol.

To find out more

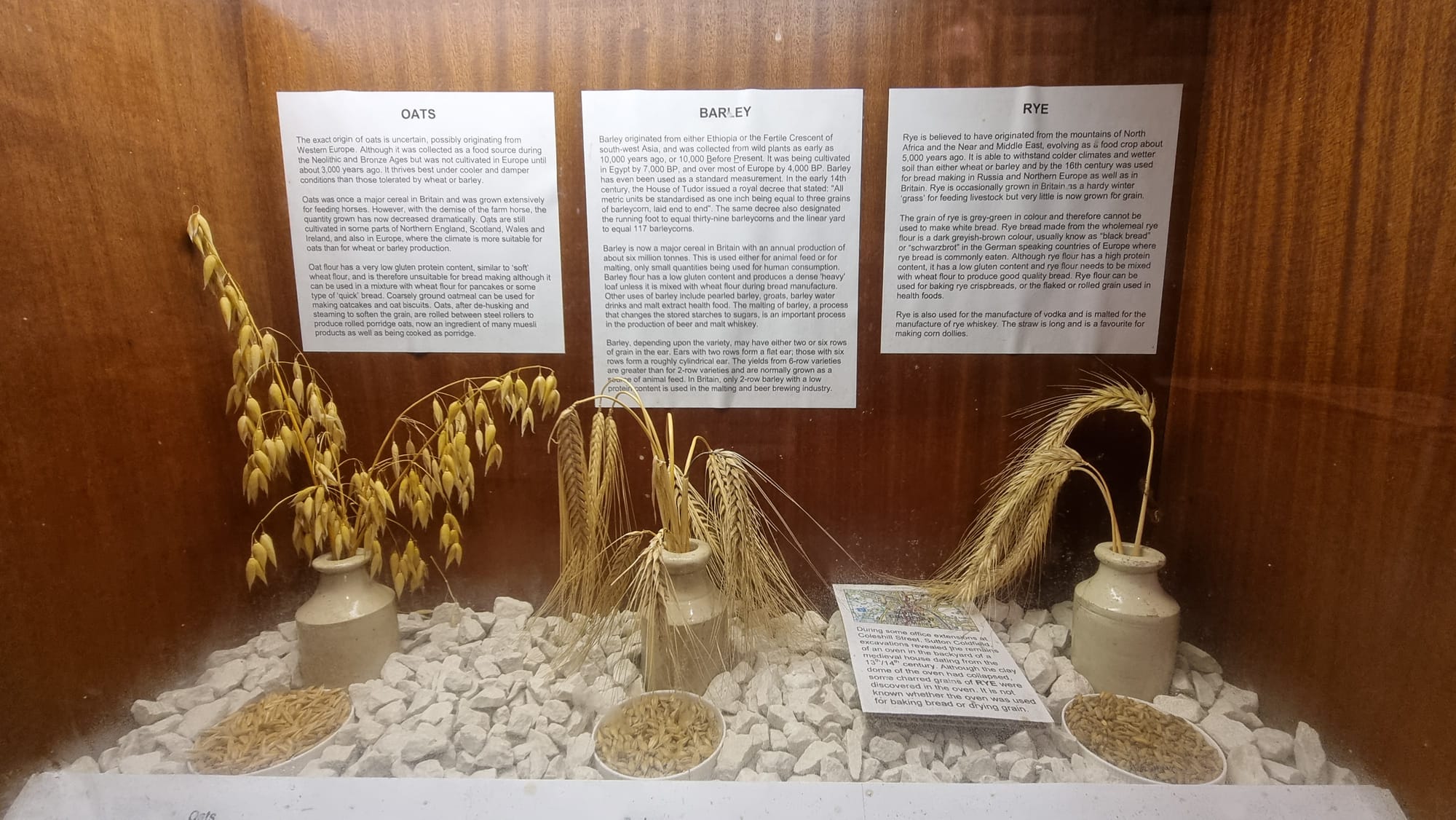

Take a look at the detailed display of cereals on the Mill's garner floor in the display area.